An American Haunting: Robert Eggers’ The Witch (2015)

The Witch, according to writer/director Robert Eggers, is an inherited nightmare.[i] Set in New England circa 1630, the film suggests that horror is an essential component of the American story, as history is viewed in art and culture as a haunted site through which we are forced to confront the past’s unfinished business.[ii] Non-historical films that are set in the past can perform similar functions as historical films, as these films offer up a reading of our relationship with the past in several ways. While The Witch does not explicitly attempt to explain this fascination with a haunted past, or what this fascination says about the present, it does find its strength in the questions that it poses—in particular about how paranoid and superstitious cultures are pulled into closer orbit with dark energy—and how it uses the past to stage a new entry into the canon of early American folklore. It is as if Eggers discovered a nearly four-hundred-year-old manuscript in the dark catacombs of a New England antiquarian society, and, drawing on the formal strength of The Shining and The Exorcist, created an immersive world that is both exotic and eerily familiar.

“What went we out into this wilderness to find? Leaving our country, our kindred, our father’s houses. For what? The kingdom of God.”

So begins William (Game of Thrones’ Ralph Ineson) in testimony against his Puritan community that he deems insufficiently pious. In this opening scene, we are treated to a montage of close shots of the faces of William’s family, barely concealing a sense of dread, that recall the paintings of Peter Paul Rubens and Nathaniel Bacon (or perhaps Dryer’s Passion of Joan of Arc which Eggers cites as an influence): their eldest daughter Thomasin (Anya Taylor-Joy), son Caleb (Harvey Scrimshaw), young twins Mercy and Jonas(Ellie Grainger and Lucas Dawson), and mother Katherine (Kate Dickie, also of Game of Thrones) stand before a colonial magistrate awaiting banishment. Their subsequent exile from the colony, presented in a POV shot from the back of their wagon leaving the plantation, foreshadows the nightmare they will soon face: the villagers, visiting Native American traders, and steel-helmet-clad guards glance back at them with suspicion and dread before the town’s gate is shut upon them forever. Months later, after carving out a new life sequestered at the edge of a forest, their newly born child, Samuel, mysteriously vanishes under Thomasin’s watch. As the family mourns over the loss, attempting to make sense of “God’s will,” madness begins to take hold—the crops begin to fail, animals behave strangely, and paranoia pits one against another.

Throughout the film, a harrowing score by Mark Korven, whose use of strings and dissonant choral music inspired by Jerry Goldsmith’s score from The Omen (1976), lends itself effectively to the cold, grey and melancholic blue-toned landscapes from cinematographer Jarin Blaschke’s, and to a deliberate, natural editing pace that avoids “jump moments” so common to contemporary horror cinema. The result is a striking example of horror as a high art, an attempt to return the genre to a status exemplified by Italian giallo films, German Expressionism, and, most importantly, gothic literature, for which Eggers displays a clear appreciation. Stephen King describes three separate levels to the horror genre: “terror on top, horror below it, and lowest of all, the gag reflex of revulsion”; terror, considered by some to be the highest of the three, is fear of the unseen, horror is the physical manifestation of this terror, and the revolting (or simply, the gross) is a shock technique.[iii] The Witch makes stellar usage of all three levels in varying ways: a sense of helplessness the film evokes, coupled with the mystery behind the evil lurking in the woods, underscores its terror elements; the film’s third act, in which the family members are resigned to their fates, is horror superbly executed; and some of the final moments are filled with images of shock horror and revulsion that stand alone as some of the most macabre in recent memory.

Carl Theodor Dreyer's Vampyr (1932)

William (Ralph Ineson) in The Witch (2015)

A crucial narrative strategy of The Witch has antecedents in film history that one would not readily expect. The Blair Witch Project (1999), The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), Wolf Creek(2005), The Amityville Horror (1979), and several others claim inspiration from true stories or, in the case of Blair Witch, provide the “documented evidence” of the true event itself—the promise of non-fiction as an attempt to break down the audience’s mental defenses. At first glance, The Witch does not appear to follow this tradition, save an end credit that proclaims that some of the film’s events are inspired by journal entries from the time. Where the film does follow this tradition is in the historical texture used as a promise of verisimilitude. The film’s period detail—hand-woven clothing, hiring an expert from Williamsburg, Virginia to build a period-precise thatched roof, and dialogue entirely in seventeenth century Jacobean English—recalls this horror film tradition but from a radically different and altogether refreshing place.

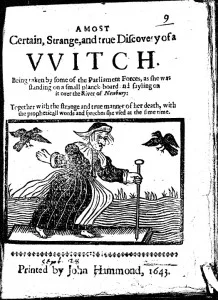

“In the period you see a lot of period sources with VV instead of W, but I’ve only seen it only larger type sizes, like the equivalent of 36-72pt. Basically if you didn’t have a W, ran out of Ws, broke your W, didn’t want to buy bigger Ws, you used two Vs.” – Robert Eggers, Reddit Q and A, February 19th, 2016.[iv]

The film’s title, printed as “The VVitch” during the opening credits, presents the film as a something akin to an old document in contrast to the Blair Witch’s found-footage. When explaining this stylistic choice, Eggers points to an actual witch pamphlet from 1643 (above left) that uses the exact same typeface used to provoke fear in Puritan American. Eggers also cites the stories of the “Goodwin Children in Boston” and the Elizabeth Knapp from Groton” as inspiration, as well as Baphomet, the symbol of the Templars, as the basis for the goat character Black Phillip (above right), who will no doubt go down in history as one of the most unnerving animal characters in cinema. Even more interesting are inspirations drawn from history that Eggers has not cited; the creeping dread that washes over William and his family, for example, is rooted in a fear of The Black Mass—a ritual in which witches gather to have sexual intercourse with Lucifer.[v] The Witch, in this sense, becomes a layered text on which the viewer can visit multiple times, deriving more enjoyment (and terror) from repeated viewings. This rich, historical texture imbued in Eggers’ frames simultaneously immerses and defamiliarizes a Puritan culture of paranoia, one of the film’s notable strengths.

By contrast, a central weakness of the film is that its ending takes a step too far. To encourage others to watch the film and make up their own mind about what they have witnessed, I will be terse. Much of the tension the film builds between itself and the spectator is over the question of whether or not there is a “real witch” or if what we are seeing is simply occurring in the minds of the characters. The film’s penultimate scene provides a near-perfect answer to this question, maintaining what Michael Phillips and Tasha Robinson describe as a balance between the literal and the metaphorical.[vi] The film’s final scene, however, further answers the question, though in way that is too bold of a statement, undercutting the ambiguity and subtly at play in the film from the opening banishment to the penultimate scene. Despite this misstep, The Witch is still a strong debut from Eggers, exhibiting the promise of a filmmaker dedicated to craft and emotional (and historical) authenticity. His next film is reported to be a remake of Murnau’s Nosferatu, and if his approach to The Witch is any indication, something wicked this way comes.

[i] “The Witch: Interview with Kate Dickie, Ralph Ineson, Robert Eggers, and Anya Taylor Joy.” Variety Studios. Sundance Film Festival. January 28th, 2015.

[ii] As scholars like myself, Robert Burgoyne, Elizabeth Bronfen, and others have written elsewhere, history is quite often presented in cinema as a haunted site populated by ghosts that still stalking the present. Though this historical haunting can be found in many contemporary historical films, I mention it in the case of The Witch as it indicates that Eggers has a firm grasp of what is at the heart of gothic horror: violence and a disturbance to the social order leaving behind a historical residue later to be confronted by future generations.

[iii] King, Stephen. Danse Macabre. New York: Everest House, 1981: 37.

[iv] https://www.reddit.com/r/movies/comments/46m0lf/im_robert_eggers_writerdirector_of_the_witch_ama/

[v] Nataf, André. The Wordsworth Dictionary of the Occult. London: Wordsworth, 1994 (original French publication 1988): 19.

[vi] In their review of the film for the Filmspotting podcast (Friday, February 19th, 2016), Phillips and Robinson draw a comparison to The Shining, noting that the ending of both films does not constitute a “twist.” Rather, both endings re-contextualize for the audience everything that they have seen up to that moment.